This article was originally published on OpEdNews on January 12, 2014.

I normally hate to make Oscar predictions. It usually depresses me. By the time the predictions start proliferating, it’s a cold matter of analysis of the awards already given out by the guilds, BAFTA, Hollywood Foreign Press Association, and (to a certain extent) the critics’ associations, like predicting presidential nominees by counting poll numbers and delegates before the conventions. You wouldn’t even need to have seen the movies first, because it tends to be a simple numbers game. I don’t much like thinking along those lines; I’d rather keep my mind on what should win.

This year is different. I actually think that, rather miraculously, 12 Years a Slave is going to win the Oscar for Best Picture. This may be the one time in Oscar history when the film which so unquestionably deserves to win actually does win.

I normally hate to make Oscar predictions. It usually depresses me. By the time the predictions start proliferating, it’s a cold matter of analysis of the awards already given out by the guilds, BAFTA, Hollywood Foreign Press Association, and (to a certain extent) the critics’ associations, like predicting presidential nominees by counting poll numbers and delegates before the conventions. You wouldn’t even need to have seen the movies first, because it tends to be a simple numbers game. I don’t much like thinking along those lines; I’d rather keep my mind on what should win.

Moreover, the selection of 12 Years a Slave brings a great many other precedents with it. It is the most uncompromising of the movies likely to be on the list of Best Picture nominees. It is not comfort food. It is not the kind of film which requires nothing of the audience, or reassures them about their own complacencies. Although the performances are amazing, they can’t be separated from the crystal-clear relevance of the film — unlike for instance, the striking, masterful, 8-category nominee There Will Be Blood (2007), when everyone talked about Daniel Day-Lewis’ fearless performance but overlooked the damning psychological portrait of an American oil baron. The directing, acting, screenplay, cinematography, editing, and music of 12 Years a Slave are all astonishing, but none of them let the viewer forget that this is a true story — an adaptation of a first-person slave narrative published in 1853 — and that it is a history churning with urgency about politics, race, and justice in America.

And then, of course, there’s the fact that director Steve McQueen would be the first black director to helm a film that receives the Oscar for Best Picture.

It’s certainly a year with an abundance of talented, thoughtful, and fiercely independent directors. (Alfonso Cuarón’s technical skill, graceful style, and boldness of vision in his gorgeous Gravity are especially impressive. Even more notable is the degree to which he turned a potentially “Hollywood-ized’ sci-fi actioner into a compelling meditation on space, our dependence on Mother Earth, and the insignificance and significance of a human life.) I feel rather sorry for Steve McQueen’s competitors, in fact, simply because they might have had better chances another year.

The director, who is about as far removed in attitude and appearance from the cocksure 1960′s movie star Steve McQueen, has actually only made 3 feature films. (Although he has directed an incredible number of shorts.) Yet this British filmmaker’s first feature clearly showed him to be an extraordinary artist, idiosyncratic and visionary. Hunger (2008), a biographical drama like no other, was jaw-dropping. He has simply continued to get better with each feature, single-mindedly carving out his own path with utterly unique projects on rock-serious subjects that few would touch. Hunger is about the 1980′s IRA prisoners’ hunger strike led by Bobby Sands: McQueen makes the concept completely visceral by boldly showing us what it looks like for a person to starve to death. His second film, Shame, mercilessly examines sex addiction, incest, and psychic pain with a minimum of dialogue and a shortage of easy answers.

McQueen’s latest, 12 Years a Slave, is a searing period drama adapted by John Ridley from Solomon Northrup’s memoir. It’s a story that, as McQueen himself has said, was crying out to be made into a film. Northrup was a free, educated, black father and husband; a prominent member of an upstate New York community; an engineer and respected violinist. Then he was kidnapped and sold into slavery in the south.

By focusing on a protagonist who has grown up free, the film is able to expose slavery anew: we can feel the horrors of it more vividly and acutely because the victim is so confident, so used to self-determination. He goes through enormous suffering, his faith and hope are destroyed, and he finds himself unable to philosophically reconcile the horrendous crime against him — yet in this way he’s a kind of witness for all slaves. Though Northrup’s kidnapping is part of an illicit commerce between the states (the process of abolition in the Northern states gave slave owners ample time to divest from their slave holdings, thereby leading many to just sell their slaves to the south), the 12 million Africans who were kidnapped and brought to the Americas before Northrup’s story even began were themselves ripped from their homes, loved ones, and sense of their own humanity in very much the same way.

Actor Chiwetel Ejiofor’s face, no matter how devastated, always reveals the free man inside. And McQueen makes clear the inner dignity of those born into slavery as well, in a variety of scenes with black supporting players — the fact that some are used to this mistreatment certainly doesn’t make it any easier on them than it is on him.

Black men on the boat traveling south try their best to overcome their terrible situation, but the odds are against them. The price of rebellion is death. Another angle is presented by Alfre Woodard, in a cameo as a privileged apple of a white man’s eye; though she plays house rather like a society matron, she bears no illusions about her status or the meaning of the slavery project as a whole — unlike the cartoonish Candyland toadies which Quentin Tarantino had so little sympathy for in Django Unchained.

It is Lupita Nyong’o, however, in a truthful and heartfelt performance as the charming, spirited, much-tormented slave Patsey, who deeply enriches the moral significance and complexity of the world Northrup encounters — and whose continued captivity when Northrup is finally freed helps ensure that we don’t regard it as an unalloyed happy ending. McQueen doesn’t let the audience off the hook.

The movie lays bare in chilling detail a great many of the mechanics of slavery, and even familiar tropes like the masters’ rapes, the wives’ jealousy, and the backbreaking toil are brought home in ways that seem fresh. McQueen’s special ability to invoke the audience’s empathy in Hunger and Shame are even stronger here, where Ejiofor’s raw emotion and spiritual pain lend a depth to his suffering that is almost Shakespearean.

Indeed, the acting is tremendous with the exception of Brad Pitt, and the visiting Canadian he plays too close to the vest (though Pitt should be commended for his vision in producing the film — getting it made in the first place.) Paul Giamatti is first-rate as the slave trader who slaps and shoves his “merchandise’ around and makes domination his business. Paul Dano is quite brave as an overseer who seethes with resentment over Northrup’s intelligence — Dano’s willingness to dig into the ugliness of such a mentality is profound . Sarah Paulson is intense as a brooding, tightly-coiled, wronged wife, full of perhaps the most virulent race-hatred in the movie. And Michael Fassbender (in his third collaboration with McQueen) is wonderful — as he always is — in a colorful, eccentric role as a depressed, alcoholic, hands-on master; his villainy is also Shakespearean, by turns red-hot and soft-spoken, powerful and needy. (In the interests of full disclosure, I must mention that his character’s last name is Epps. Since this is based on a memoir and that might be the real slave master’s name, I pray that there’s no relation.)

There’s such a subtle, wide-ranging understanding of racism in the film, it really is provocative in the way it challenges viewers on issues of personal accountability for social wrongs. The versatile Benedict Cumberbatch is Ford, Northrup’s first master after the kidnapping. Ford is an intelligent and feeling man who admires the special musical and engineering skills of his slave — but he still gives him a violin instead of freedom. Ford’s complicity in the injustice against Northrup is one of the finer points made by the film; Ford sees how much suffering the slave market creates, but he makes only the merest peep and then drops his complaint. (The agony caused by separating parents from their children is an extended topic of the film.) Ford is also impressed, and takes advantage of for the benefits to his business, Northrup’s exceptional levels of education. But when Northrup tries to tell him that he’s a free man, Ford exclaims “I cannot hear that!”

The question of “what did they know and when did they know it?” is a strong ethical refrain of the movie — since everyone that Northrup meets, like the cast of characters in a Dickens novel, ends up skewing either cruel or kind, trustworthy or treacherous. 12 Years a Slave answers that question, implicitly as: they all knew, everything, and they knew it early. They knew that slaves weren’t really happy, that slavery was earth-shatteringly unjust, that their workers were intelligent and soulful fellow humans rather than property (Fassbender keeps repeating the word “property” as if needing to convince himself). Numerous instances speak to this knowing: characters can quite plainly see Northrup was born free, yet they go ahead and deprive him of his human rights; Patsy’s master believes he has a special regard for her, but treats her brutally; a distraught enslaved mother is told she will soon get over the separation from her children, but when she doesn’t, her grief — and the powerful evidence it thrusts on the white folk that she is, actually, just like them — makes her expendable.

Some long-standing contradictions of slavery are enumerated in the film: if slaves were naturally subservient, why would their spirits need to be broken; if blacks were so intellectually inferior, why would literacy among slaves be such a threat; if all God’s children were equal, how could Christianity be applied so differently to whites and blacks; and so on. (Fassbender even formally preaches scripture to his slaves, explaining to them that he is the “Lord” referred to in the text.)

We are also frequently reminded that this whole enterprise was very much a business. This story reveals a little-known activity within the U.S. slave trade that seems particularly striking in its outrageousness: kidnapping free black northerners and selling them into slavery down south. The kidnappers are so perniciously, smoothly evil — they win Northrup’s confidence by complimenting him, deceiving him into believing that they respect his education and sophistication — that the shamelessness of the way they make their profit is even more horrifying. They know, more than anyone else in the entire film, what they are putting Northrup and others through.

Most of the film is very naturalistic, but an early visual uses computer-generated imagery to make an ironic social comment. After Northrup has been drugged and kidnapped, he is held in a cell and beaten. When finally left alone, he cries out desperately for help. McQueen carries us outside to the rooftops of the 19 th century Washington, D.C. skyline. At the very top of the skyline is the Capitol building. Though a potent symbol of democracy, Northrup receives no protection from it.

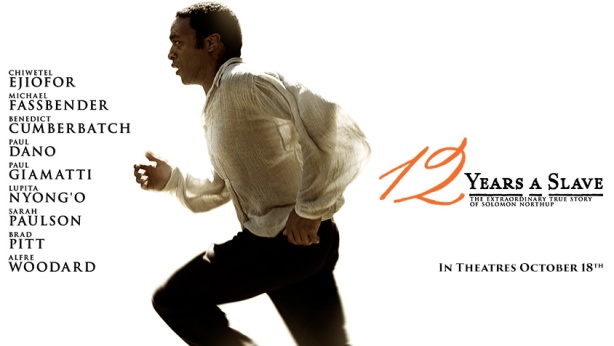

The movie poster shows Northrup running, but this is not a movie about a fugitive slave — he doesn’t get that chance. He’s always stuck on a plantation, and the movie reveals how fully white society conspired to keep slaves stuck there. Even the abolitionists or friendly whites in the film seem to be scared of that powerful system. (David Blight, a Yale expert on the history of slavery, describes that system as “a police state.”) The poster’s image actually comes from a revealing moment in the film when Northrup is sent on an errand alone, and it occurs to him that now he might escape. He’s wrong, however; he soon comes upon some white men hanging blacks from trees, and he quickly realizes that not only is he powerless to help his brethren, but without the note from his mistress, his own life would have been of no worth.

Yet a couple of scenes later, McQueen teases us again over our Hollywood-reared naïveté . He cuts to Northrup running through the woods once more. We’ve just seen how deadly it would be for him to run away, how impenetrable the barriers are. Yet we still hope that he’s broken free; we’ve been spoon-fed so many popcorn movies of heroes triumphing over gigantic obstacles. Though of course Northrup is resilient and courageous, and that’s how he survived, he’s only a human being. He happens to be running simply to reach the place he has been sent to faster; to summon Patsey back to their master.

That one moment encapsulates how eloquently McQueen reminds us of how much we have forgotten — how much we have averted our gaze from so as to avoid the pain of remembering that shameful legacy. 12 Years a Slave deserves to win the Oscar for Best Picture not just because of its artistic excellence or the ground-breaking precedents it will set, but also because it preserves for posterity a crucially significant part of world history. It’s a history we ignore at our own peril.

Awards Update:

12 Years a Slave is now the winner of the Golden Globe Award for Best Picture — Drama. (It was also nominated at the Golden Globes for three of its performances and for Directing, Screenplay, and Original Score – tying with American Hustle for the most Golden Globe nominations this year at 7 apiece.)

12 Years a Slave has already won Best Film trophies from the American Film Institute and from numerous local critics associations around the country.

It also has 13 Critics Choice Awards nominations, 10 BAFTA nominations, 10 Satellite Awards nominations, 9 London Critics Circle nominations, and 7 Independent Spirit Award nominations.

Director Steve McQueen’s first two films won numerous international awards as well, including the Venice Film Festival’s FIPRESCI prize.

No comments:

Post a Comment