POLICY

Chimps as Experimental Subjects

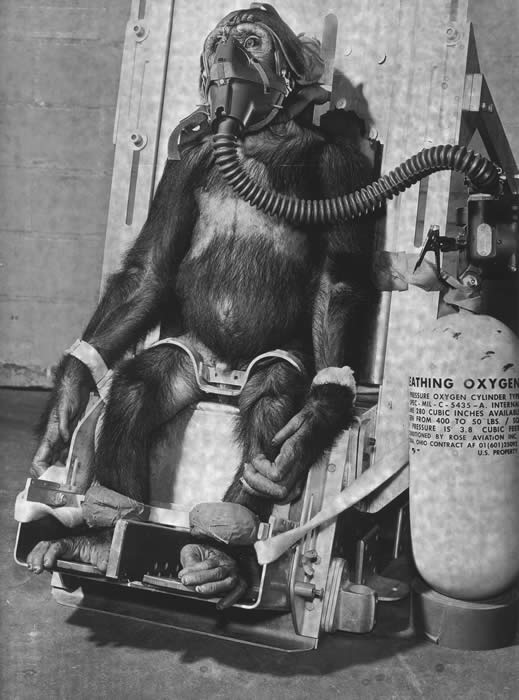

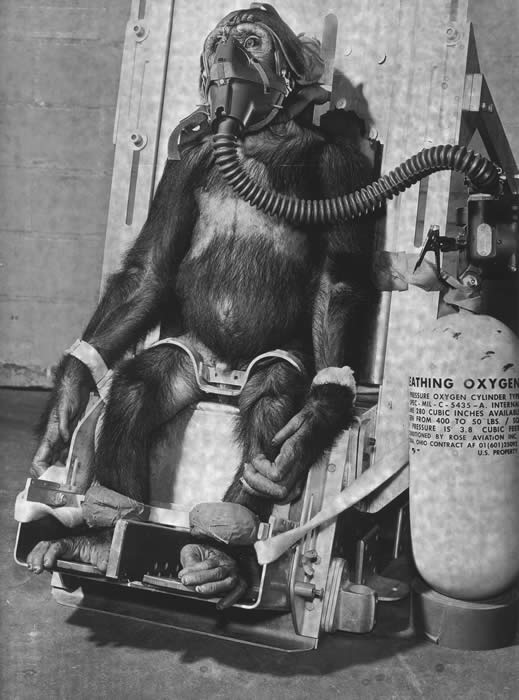

The U.S., the only developed country still using this species in invasive medical experiments, has now taken significant strides toward cutting down their use by labs. First, a December 2011 Institute of Medicine report commissioned by the National Institute of Health (NIH) concluded that "€˜most current use of chimpanzees for biomedical research is unnecessary"€™. A committee of experts then set about scrutinizing all NIH-funded projects making use of chimps. Within 9 months, the NIH authorized the retirement of 113 government-owned chimpanzees, and began transferring them to sanctuaries. Moreover, in January of this year a NIH task force of scientists, the Health Working Group, deemed laboratories unable to meet the needs of chimpanzees and called for a halt to the breeding of chimpanzees and a gradual end to existing biomedical research grants for projects with chimps. They recommended the government retire 300 other chimps from its labs, suggesting just 50 chimps be retained for possible future experiments.

This is long-overdue progress and will have a real practical effect on the quality of life of these chimps. This is clearly evident from

footage this spring of freshly released NIH research chimps seeing sunlight and the outdoors for the first time after decades of incarceration. However, if invasive research and the keeping of chimpanzees in laboratory facilities is inhumane, then it'€™s just as inhumane for the unfortunate 50 chimps who have to stay behind. And Stephen Rene Tello, the executive director of Texas-based sanctuary Primarily Primates, has other concerns, since the government is maintaining ownership of all the chimps. "€œWhat happens if someone decides they suddenly need chimpanzees for research again?€" Tello fears: "they'll send them right back to the labs."

Meanwhile, research on chimps continues in the private sector. While the efforts of animal protection agencies have raised awareness, and a string of pharmaceutical companies such as Idenix Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk and Gilead Sciences, Inc. have

promised not to use chimps in their research, there are still 950 chimps in labs in the U.S. being used as industrial test subjects.

Thankfully, a strong

movement exists to persuade Congress to pass the Great Ape Protection and Cost Savings Act, a bill to

ban the use of chimpanzees in invasive research (and save the Treasury $250 million dollars in a decade). The Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM), a group that both opposes vivisection and advocates for human health (and whose legislative leader is Dennis Kucinich's wife Elizabeth), is one of the organizations passionately campaigning for this bill, which has been introduced by allies in session after session. PCRM reports the encouraging

news that the bill garnered record support in the 112th congress, with close to 200 co-sponsors in the House and Senate. Its supporters will be back to try again. The film world and Washington politics meet here, as James Franco, the headliner of Rise of the Planet of the Apes, also endorsed the Great Ape Protection and Cost Savings Act in this PCRM

video.

Chimps as Entertainers

The world of entertainment and policy intersect in another way where great apes are concerned. An international campaign is afoot to end the use of great apes as performers in entertainment (chimps and orangutans being the ones generally used) and it is spearheaded by tireless chimpanzee champion Jane Goodall, as well as by national animal advocacy groups such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS). The opposition stems in part from the fact that there is no way to police how the animals are trained -- though the American Humane Association (AHA) monitors the treatment of animal performers while they're on set, no-one assesses the techniques the trainers use in private to condition the animals to obey their commands. (And moreover, there are numerous

criticisms of the integrity of the AHA's monitoring operations, which have very limited authority and which are financed by the studios themselves.)

Plenty of

incidents have been recorded of

routine brutality toward ape actors, who begin their careers at very young ages, while they can still be dominated by human beings. The

allegations of chimp abuse on the set of 2008's

Speed Racer are just the tip of the iceberg. Primatologist Sarah Baeckler, who

witnessed a culture of beatings of young performing chimps as a volunteer at Amazing Animal Actors ranch in Malibu, points out: "Healthy, young chimpanzees are playful, curious, energetic, and mischievous, but these traits don'€™t serve them well when training begins, so one of the things that chimpanzees in the entertainment industry have to endure is an initial 'breaking of the spirit'.€™ In other words, they have to learn how NOT to act like normal chimpanzees." Baeckler goes on to state that "abuse and physical violence are seemingly commonplace in this industry, and it'€™s not even a secret. In fact, it€'s taught in a training school [Moorpark College's Exotic Animal Training and Management program] that is currently producing many future animal trainers and zoo workers."€ One indicator of how prevalent the abuse may be is the ubiquitousness of chimp performers €'grin' - far from being gleeful, that grimace on chimpanzees is an expression of fear.

When apes get older they are no longer manageable even by brutes (typically, an 8 year-old chimp is already too dangerous to keep), and so they are sent to live somewhere else, often a sub-par roadside zoo where their housing and care are inadequate and they are isolated and bored. (Decent, accredited zoos won'€™t accept them because apes in such zoos now live in group installations, and chimps reared among humans are at sea in the complicated dynamics of chimp society; they can'€™t protect themselves from the aggression of dominant chimps.)

If they are lucky enough to end up at an enlightened ape sanctuary, this places the burden for their care on the philanthropic animal-charity community. The trainers who profited off of them (and traumatized them) just go on to acquire other young chimps.

And there are even more far-reaching reasons to ban the use of ape actors. A 2008 survey found that the public is less likely to think that chimpanzees are endangered compared to other great apes. This may well be partly because chimps are so familiar to viewers from their use in commercials, circuses, and on greeting cards. (The truth is all four types of great apes are endangered.) A

2011 study by Ross et al. has shown the power of even simple imagery: participants who were shown photos of a chimp standing next to a human were 35.5% less likely to deem chimpanzees as endangered or declining than those who saw photos of chimps alone.

These images can also boost the pet trade: participants who viewed these photos of chimps coexisting with humans were 30% more likely to believe that a chimp would make a good pet. (Charla Nash, the Connecticut woman who was

attacked by former-performer Travis in 2009, would beg to differ, since her encounter with the 200-pound male chimp resulted in her face and hands being ripped off; she is now blind, has had a full face transplant, and now has to live in a nursing home at age 57).

Some celebrities have taken a stand against the use of ape actors in entertainment, like Angelica Huston, Alec Baldwin, Cameron Diaz, and Bob Barker. And public pressure campaigns have convinced numerous companies --€“ including Capital One, Dodge, Pizza Factory, and Pfizer -- to can chimp ads for good.

However, Career Builder has been for several years one of the most prolific employers of chimpanzee performers through its series of humorous, office-based, TV ads.

Even though the trainer of the chimps used in the ads has been excoriated for cruelty by animal activists -€“- and his first round of chimps has already been shuffled off to sanctuaries -- Career Builder has taken a defiant stand for several years when faced with

complaints against its ads. For example, Stephen Ross of Lincoln Park Zoo's Fisher Center for the Study and Conservation of Apes in Chicago has submitted his objections to Career Builder every year since 2005 without receiving a reply. (This is in spite of the fact that a

Duke University study found that the ads were not even very effective.)

But there may be some good news: in 2013 Career Builder

refrained from buying air time during the Super Bowl, as they had so often done. It is still too early to tell whether they will stop using chimp performers. They have made no such promises.

PORTRAYAL ON FILM

And there is yet more on the plus side, especially for those who care about film and its social impact. Listed below are five recent movies, straddling a range of genres, which depict chimps in enlightened ways which communicate that our evolutionary siblings are highly social, intelligent, and sensitive animals. Two of these movies are strong indictments against conducting medical research on chimpanzees, and none of these films utilize trained chimpanzees as performers. Instead they used performance capture, puppet animatronics, documentary file footage, patient nature photography, and claymation.

The filmmakers here often employ a shorthand which suggests that they believe the audience already has a high level of respect for chimpanzees, and that it is ready to believe in quite sophisticated simian abilities. This is very encouraging because it is surely an inevitable step from that belief to a conviction that chimpanzees deserve far better treatment from us.

Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011)

Directed by Rupert Wyatt; with Andy Serkis, James Franco, Freida Pinto, John Lithgow, and David Oyelowo

This blockbuster reboot of the 1968 - 1975 franchise of films and TV programs has a very powerful resonance with current animal rights thinking. It recasts the story of Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972) inventively and believably: unlike the original series in which apes came to gain human skills gradually, Rise of the Planet of the Apes shows a chimpanzee becoming super-intelligent virtually overnight, thanks to an experimental gene therapy which speeds up neurological development. Thus the filmmakers are not just floating around in a purely hypothetical sci-fi ether, they are basing their speculative fiction on the fact that chimps already often score at the level of young human children on psychological and intelligence tests. The circumstances under which this gene therapy gets discovered are also realistic: the motive is profit, a pharmaceutical company which experiments on chimps in trying to find a cure for Alzheimer's.

This adds up to a terrific solution to the problem that had plagued numerous directors and writers trying to find a way back into the franchise. Peter Jackson, Oliver Stone, James Cameron, Sam Raimi, and the Hughes brothers all tried to crack that nut at some point. (Nut-cracking being a type of tool use which it turns out we share with

Pan troglodytes.) I believe that director Rupert Wyatt and the screenwriters, Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver, succeeded where others failed (including Tim Burton in his decent but rather uninspired 2001 rehash) because they genuinely tried to see the world from an ape'€™s point of view. And since they were prepared to get real about how deplorably we treat these animals, they didn'€™t have to invent an alternate civilization and the layers of legend and custom some of the earlier films in the series did.

Rise of the Planet of the Apes is very similar to our own society, and how we subjugate apes

right now. The main difference between the real world and the movie’s is that in the film the apes can do something about it.

Rise came out of nowhere to wow audiences and that wasn'€™t just because of exciting action sequences or extremely convincing special effects. Surely one reason this film defied expectations was because no-one had anticipated how strongly it would provoke

empathy with its animal hero. Usually films that make the plight of an animal central are meant for kids (though now with the addition of

War Horse to the game as well, that may be changing). But

Rise is an adult and weighty film that avoids sentimentality. And even though it gives apes abilities they don'€™t normally have, it more or less transcends anthropomorphism by showing how those abilities are acquired in practical terms. And also by building a sophisticated awareness of Caesar'€™s wishes and desires, all of which are completely believable. Caesar is not out to take up tap-dancing or learn kung-fu. Caesar and his comrades just want freedom and dignity, and they want it on simian terms --€“ they're not campaigning for better pay; they just want to get out of their cages, get away from their abusers, and go live in some trees.

The original Planet of the Apes franchise consciously evoked the hotbed of race relations that marked that era. There are still some references to those symbols in Rise: the types of oppression we see; the way in which the rebellion develops; the classic line "€œTake your stinking paws off me, you damn dirty ape"€; the loaded image of a water hose being used as a weapon. And the revolution in Rise begins as a prison revolt led by Caesar -- which is not just a look back at Attica, but has contemporary relevance too (as witnessed by the week-long prisoner strike in six Georgia prisons the year before Rise came out).

But when Rise begins with a young chimp being forcibly captured in the African jungle, traumatically ripped away from his mother, it seems to be making "€œthe dreaded comparison"€ - the comparison, to cite Marjorie Spiegel'€™s term, between human slavery and animal slavery. This feeling, that the oppression of animals in Rise is not just an analogy for something else but the thing itself, continues to be felt in the brutality of the medical lab scenes and the 'prison'€™ scenes at the animal shelter.

Whereas the 1970's Planets movies often cast people of color in mediator roles --€“ they often empathized with the underdogs because, it was implied, they understood it from their own history -- only Freida Pinto comes close to fulfilling that role in Rise. (She'€™s a vet who loves chimps.) But her role is essentially decorative. More key to the plot is Jacobs, the black CEO of the pharmaceutical company (David Oyelowo). He impacts directly on the apes'€™ future. And he actually has no empathy for the oppressed. He is driven by the profit motive, and has no feeling for the chimps at all --€“ or even for the well-being of society. He just wants his company to patent a cure for Alzheimer'€™s because it'€™s lucrative. His presence suggests the debasement of political consciousness in a consumerist paradigm; but it also underscores the notion that the apes are the most oppressed group in the movie'€™s class system. Being human, no matter what your race, brings you great privileges compared to animals'€™ lot. Being human makes you ultimately blind to the suffering of those who are non-human.

But beyond issues of the oppression of certain groups, Rise also makes us aware of the idea of consciousness within an individual. Rise differs from its 1972 predecessor Conquest of the Planet of the Apes in that we see Caesar acquire language skills as a young chimp (the filmmakers can rely on our knowledge of sign language experiments with apes; it isn'€™t remarkable to the movie'€™s scientist-hero that Caesar learns signs, merely that he learns so many, and so quickly). And we are able to see Caesar'€™s coming-of-age through his self-awareness. While little, he feels safe and secure in his adoptive human family, but one day when he is older, he notices that humans take their dogs for walks on a leash --€“ and that he too is on a leash. It occurs to him for the first time that maybe he is "a pet."€™ In this stirring moment he becomes conscious of himself in a new way; he begins to feel loneliness and resentment not unlike what the Creature in Frankenstein experiences when he realizes that he will never actually truly belong to human society.

The other similarity Rise has with Frankenstein is the theme of science run amok --€“ after all, the researcher played by James Franco inadvertently brings on the demise of human civilization by messing with chimpanzee brain chemistry. Unfortunately, this theme is rather commonplace and mundane (you’ve seen it over and over again, from the John Lithgow thriller Raising Cain to the monster movie Jurassic Park). The root of it seems a little superstitious: as if you€'d better not '€˜play God'€™ or God might punish you. It'€™s the kind of thing that sparks Christian fundamentalist opposition to stem cell research.

But what Rise does that I find more gratifying than the Frankensteinian retread is that it vividly condemns the use of chimps in medical research. Even without enhanced brain-power, it is clear they are suffering in the lab. Moreover, the gene therapy that Franco tries out on his Alzheimer'€™s-diagnosed father (Lithgow) begins well but soon starts to make his dad fatally ill, because it does something far different to humans than to apes. In other words, the filmmakers take as a key plot device the very argument anti-vivisectionists make when they are trying to appeal to people on practical terms: humans and non-humans are not biologically identical, and testing substances on non-humans still doesn'€™t make them safe for humans. (Chimps may be our closest relatives, but that doesn'€™t mean they get menopause, breast cancer, or prostate cancer, to name a few differences.) Rise also warns us that research run by the private sector on purely capitalist principles has strong potential for greed, short-sighted thinking, and irresponsibility.

Who knows if the sequel to Rise of the Planet of the Apes will comment so directly on the current plight of great apes. Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, which is currently filming and slated for a 2014 release, reportedly takes place in the midst of the plague decimating the human population of Earth -- set up briefly in the exciting coda to Rise. The film has different faces (Jason Clarke, Keri Russell, Judy Greer, Gary Oldman) and will not be directed by Wyatt again. Moreover, two additional screenwriters have padded the list of writers out to four. This is a little worrying in terms of what the movie'€™s focus might be, but it is encouraging to learn (as I did at a public lecture on primates on Darwin Day) that the makers of the film consulted with leading primatologist and spokesperson for ape conservation Dr. Craig Stanford, the author of Planet Without Apes and co-director of the Jane Goodall Research Center at USC.

It is also reassuring that Dawn of the Planet of the Apes will bring back the true star of Rise, the British-born character actor Andy Serkis --€“ now best known for iconic motion-capture roles like Gollum, King Kong, Tintin'€™s buddy Captain Haddock. The content of Rise is terrific, and the incredible realism of the special effects is the best argument against using actual apes as performers, but what really makes this a film that can change hearts and minds is the depth and delicacy Serkis brings to Caesar'™s internal life.

Project Nim (2011)

Directed by James Marsh; with Nim Chimpsky, Herbert Terrace, Bob Ingersoll, Stephanie LaFarge, and Cleveland Amory (as themselves).

James Marsh, the director of the impish, Oscar-winning documentary

Man on Wire, also won documentary awards for

Project Nim from Sundance, the DGA, and the Boston Society of Film Critics. He has assembled this film adaptation of Elizabeth Hess'€™ non-fiction book

Nim: The Chimp Who Thought He Was Human from a wealth of archival footage, interviews with the key players in this peculiar 1970'€™s history, and occasional dramatic recreations using animatronics. In press on the documentary, Marsh has pointed out how unusual it is for a film to tell the biography of an animal (though the documentary

One Lucky Elephant was released around the same time and did something similar). Indeed, the important

Project Nim comes as close to letting Nim Chimpsky tell his own harrowing and heart-wrenching story as a film about a chimpanzee can perhaps do. Nim was the famous male chimp who, as a baby and young child, was the subject of behavioral psychologist Herbert Terrace'€™s headline-grabbing ape language study -- Terrace set out to teach Nim ASL as part of a Columbia University experiment.

But when Terrace rather abruptly ended the project and the cameras went away, Nim'€™s story turned bleak and Dickensian: snatched from any human family and thrust into a cage in a primate center, shocked with an electric prod to discipline him; then, soon after, sent to a lab doing invasive research to test vaccines. The way Project Nim operates, in fact, is quite close to a Dickens novel: by asking us to empathize with the hardships undergone by a waif growing up in a cold, cruel society that doesn'€™t understand him, we are given what we need to realize how many like him must still suffer in similar ways. Whether Marsh intended it or not, Project Nim is a strong argument for reform.

Despite the subtitle of the source material for the film, being a €'Chimp Who Thought He Was Human'€™ was not really Nim'€™s problem. It was the ways in which he was treated like he wasn'€™thuman that were the real problem. In short, the way chimps in captivity are treated all the time. He was stolen from his mother at 2 weeks of age (which was cruel to her too, especially since that had already happened to her 6 times), he was enculturated into a human family and then abandoned by that surrogate parent too (a free-spirited woman who'€™d actually insisted on breast-feeding him). In a short space of time he was abandoned by another surrogate mother, then another, then his first male friend. And so on. He was eventually removed (through deception) to a new and utterly foreign location, and banished from human culture to find himself at sea in a bewildering and dangerous hierarchy of apes --€“ creatures he'€™d grown up the last few years without ever laying eyes on. (It seems quite likely the makers of Rise of the Planet of the Apes read Nim'€™s story as research, because Caesar goes through an almost identical trauma.)

One of the most disturbing moments in this ground-breaking film comes when it is revealed how many chimpanzees who had participated in a fad of sign language instruction and human enculturation projects ended up in medical research labs. The chimps try to sign to the human lab workers in vain --€ the staff don'€™t speak sign --€“ and when a lexicon is developed to understand what the chimps are trying to communicate, it turns out the chimps have been signing such words as "€œkey," "open,€" "out," "€œshoes," "€œplay," and "€œhug."€ These are the same beings who the lab workers strap down to tables to draw blood or to give injections; not only do they look very human in those supine poses, but they also look disarmingly like Christ on the cross. Meanwhile, Marsh includes powerful testimony from Dr. James Mahoney, a scientist who oversaw the lab in question and who ultimately became a bit of an Oskar Schindler. Mahoney himself points out that given apes’ intelligence, keeping them in medical labs "€œcan'€™tbe humane."

The whole section on Nim's incarceration in the research lab is gripping; numerous people work behind the scenes to try to rescue him from there, but it'€™s very difficult because --€“ and this is another way, of course, that Nim was treated differently than a human being -- he isowned by others. He is chattel. The film doesn’t get into the '€˜personhood'€™ question, but it lays groundwork for it.

Marsh does an admirable, deeply moving, highly disciplined job creating empathy for his eponymous chimpanzee. (There's never a moment of sentimentality or polemicism.) Still, I think he neglects context that his subject matter cries out for. When Terrace comes out with the bold conclusion that Nim never did acquire language skills but merely "€œlearned how to beg"€, Marsh includes TV footage of the announcement but returns quickly to Nim'€™s predicament. Marsh doesn'€™t give Terrace'€™s detractors in the ape language study community a voice --€“ even though Terrace'€™s pronouncements had a far-reaching negative effect on their own work, including, I suspect, on their funding.

Perhaps one reason for Marsh'€™s decision can be gleaned from interviews he gave to promote the movie; he doesn'€™t seem to believe that Nim was ever capable of learning language. The documentary itself contains plenty of nuggets that seem to attest to the contrary: Nim signs spontaneously at all of his foster homes, trying to get humans to respond to him; one of Nim'€™s companions, Bob Ingersoll, recalls when they hiked together and Nim would sign to him: "œHe talked about trees, berries he found"€; after a long separation, when Nim sees Bob again, he immediately starts signing to him; when Nim eventually gets a lady-chimp roommate, he teaches her signs. But Marsh seems to accept Terrace'€™s interpretation of Project Nim, perhaps afraid to question his scientific expertise. (This despite the fact Marsh frequently presents Terrace as a very unattractive personality, and his experimental structure as completely slapdash and chaotic).

This acceptance is especially regrettable because the book Marsh used as the film's basis draws a

different conclusion. "Nim had a vocabulary. He learned all these signs, and he could communicate with them," author Hess says. Hess also provides significant background on ape language studies in her book, so Marsh can'€™t plead he was ignorant of other scientists'€™ claims. Yet the numerous scientists who have conducted much longer-range studies than Terrace (not only on chimps, but on gorillas, orangutans, and even the much less well-known species, bonobos) are notably absent from the film.

Anyone who has watched enough footage of Francine Patterson signing with Koko the gorilla, for instance, can readily see why Terrace may have gotten very different results from hers. What is most striking about Patterson'€™s recorded interactions with Koko (evident in various TV specials but most remarkably in the 1978 Barbet Schroeder feature Koko, a Talking Gorilla) is how fully Patterson gives Koko her undivided attention, how she treats her as a mind on the same plane as her own. It is the way the most effective teachers talk to children --€“ with respect, with affection --€“ rather than the way adults who don'€™t like kids will talk to them patronizingly, domineeringly, or confrontationally. Koko is not '€˜the gorilla who talked' so much as Patterson is the human who listened; and even if Marsh doesn'€™t realize the significance of it, his Project Nim documents how deplorably Terrace failed to do that.

The Pirates! Band of Misfits (2012)

Directed by Peter Lord and Jeff Newitt; with Hugh Grant, Martin Freeman, Imelda Staunton, Jeremy Piven, Salma Hayek, and Ashley Jensen

This claymation film by Aardman Animations, the irrepressible British studio known for the Wallice and Gromit characters and the delightful Arthur Christmas, is a Monty Pythonesque pirate romp through Victorian times adapted by comic writer Gideon Defoe from his own children'€™s novel. (The original title is charmingly inelegant: The Pirates! In an Adventure with Scientists! ) Anchored by an almost unrecognizable vocal performance by Hugh Grant as the Pirate Captain (perhaps the best comic delivery in his career), the movie was nominated for an Academy Award and a European Film Award for best animated film. It is not a film about a chimpanzee like the above two features were. But it does have supporting characters who make it relevant to this discussion.

This comedy features a hilariously irreverent take on Charles Darwin (posh but whiny David Tennant) as a nerd who has spent so much time dissecting barnacles he has no love life --€“ and as a schemer who will stoop to anything to get ahold of the pirates'€™ prize possession, a dodo. This deliberately wacky 19th century free-for-all is not meant to be historically accurate, which is part of its giddy appeal: a dodo has somehow appeared several hundred years after they went extinct; the Elephant Man shows up alongside Jane Austen, though they were decades apart; the pirates engage in an annual contest for best pirate and the emcee dresses like Elvis; and the Pirate King mimes to a friend "€˜phone me€". But my favorite anachronism is the fact that Darwin, straight off the ship and before he even has an inkling of his landmark theory, is keeping a tame chimpanzee in his townhouse and teaching him human culture and language just like a psychologist in the U.S. in the 1970'€™s might have done.

This chimpanzee, Mr. Bobo, becomes a key character in the film -- part butler, part henchman, all-brain (he'€™s often the sanest and most resourceful '€˜person' in the room, not unlike the servant character in a lot of classic plays). Of course that is anthropomorphism, but the movie sets up a logic for it akin to the dog-translator collars invented by the mad scientist in

Up. Mr. Bobo doesn'€™t speak, per se, he just holds up cards silently to comment on the action. This is satisfyingly redolent of methods used by scientists in real life to teach the bonobo Kanzi -- who is said by primatologist Sue Savage-Rumbaugh to know 384 words/symbols (lexigrams taught to him on computer-based keyboards).

The filmmakers at Aardman exploit their Charles Darwin character (with great affection) for some of the funniest gags, in a comedy that is already very funny. At one point, the Pirate Captain responds to pre-Origin of Species Darwin'€™s moping and depression with: "We didn'€™t evolve from slugs just so we could sit around drinking our own sweat." Yet Darwin fails to pick up on the clue. In another scene, Charles and his chimpanzee sit side by side in a bar eating bags of '€˜monkey nuts'€™. The Pirate Captain sees something in them for a moment: "€œAre you two related? There is a resemblance."

And Band of Misfits not only features a smart chimpanzee and a sweet, pudgy dodo (who doesn't speak, and whose behavior is believably bird-like), it also comes up with a villain who is even nastier to animals than Cruella de Vil of 101 Dalmations (or the rabbit-hunting Lord Victor Quartermaine in Aardman'€™s own, also animal-friendly, The Curse of the Were-Rabbit). I won’t give it away, but the villain'€™s dastardly scheme cleverly allows this irrepressible film to both mock the rich elite and skewer ignorant, selfish attitudes toward rare animals.

The nightmarish medical experimentation on chimps we see in Rise of the Planet of the Apes and Project Nim doesn'€™t come up here --€“ perhaps because the often animal-oriented Britain stopped using great apes for medical research in 1986 -- but at the end of Band of Misfits, like at the end of Rise, the chimpanzee who has learned to communicate from a scientist surrogate-dad doesn'€™t choose to stay with the human parent who raised him. Mr. Bobo, like Caeser, chooses freedom.

Chimpanzee (2012)

Directed by Alastair Fothergill and Mark Linfield

This Disney Nature documentary follows the trials and tribulations of a 3-month old male chimp child who lives with a troop of wild chimpanzees in the forest in Gombe National Park in Tanzania. Oscar loses his mother due to inter-tribal warfare, and, orphaned, he is treated as a pariah by all other members of his simian society until, too young to fend for himself, it seems certain he will die. His sudden adoption by Freddy, the alpha male of the troop, is a dramatic and moving turnaround that provides a beguiling glimpse into the mysterious intricacies of chimpanzee emotions.

Much of the ethology we've come to know about chimps is on display here, a kind of refresher course --€“ albeit in a wholeheartedly commercial package €-- of chimpanzee hunting parties, warfare, tool use, imitative learning, social hierarchies, and the complexity of their culture. The aggressiveness of adult male chimps on display here is probably helpful in the attempt to get the word out that chimps do not make good pets. Moreover, the clear impact of the loss of his mother on Oscar can help build abhorrence against chimps being taken from their mothers -- as we have so callously done for our own purposes. Tim Allen'€™s slangy and jokey narration is sometimes annoying, and the film is no March of the Penguins, but it works fine as a traditional Disney nature doc.

Creation (2009)

Directed by Jon Amiel; with Paul Bettany, Jennifer Connelly, Benedict Cumberbatch, Jeremy Northam, Toby Jones, and Bill Paterson

Creation is an intriguing, literate, and pointedly well-acted slice of domestic life at Down House, the estate where Charles Darwin (Paul Bettany) lived with his wife Emma (Jennifer Connelly) and their household of children. The fact that Charles'€™ radical theory threatens to turn Victorian religion upside-down, while Mrs. Darwin is a devout and traditional Christian worried for his soul, brings pretty high stakes to the marital conflict. And things get even more complicated between them when the Darwins'€™ 10-year old daughter Annie dies of illness; the screenplay was adapted from the non-fiction book Annie's Box by the conservationist and great-great-grandson of Darwin, Randal Keynes. It focuses on Darwin's relationship with his favorite child, and how he and Emma interpret her death. A punishment for hubris? The result of over-reliance on science? (Darwin is convinced Annie'€™s scarlet fever should be treated by strong doses of a new Victorian discovery, the '€˜water cure'€™. This keeps her damp and shivering almost constantly.)

Director Jon Amiel surrounds the biographical scenes of Charles'€™ personal and family life with an expansive philosophical questioning: he lets it be disturbing that nature is cruel, that animals in the wild are constantly preyed on by other animals; he doesn'€™t exclude the existential "Well, what'€™s the meaning of life then?" angst provoked by a theory of randomness behind creation.

At the same time, the act of "creation"€ in the title also refers to the process by which Darwin arrives at his big idea, and like some other films about geniuses, it is exciting for that reason alone. And one scene in particular shows that the film'€™s heart is in the right place: Darwin spends an afternoon at the London Zoo in a room with a baby orangutan, taking notes. (The visit really happened in 1838.) Amiel has the good sense just to turn the camera on a baby orang playing with Bettany and leave the two of them alone; the infant'€™s natural curiosity and playfulness shows much greater intelligence and human-like emotion than a trained ape performing tricks could do. (I'€™m pretty sure that films like the Clint Eastwood-orangutan buddy picture Every Which Way But Loose never wanted us to be impressed by ape intellect anyway: as the Canadian scientist and broadcaster David Suzuki pointed out many years ago, the purpose of animals clowning in circuses and the like is actually to make us feel superior to them; the charade, the artificiality of their behavior, is part of the message.)

Though it was released on the 200th anniversary of Darwin'€™s birth,

Creation doesn'€™t feel like a definitive drama about the amateur scientist. As the late Roger Ebert

wrote: Darwin and the Mrs. don'€™t "€œfully debate their differences...The filmmaker, Jon Amiel, obviously has great respect and affection for the scientist--for them both, really... [But]

Creation dares not state relevant ideas that were acceptable nearly 50 years ago, when

Inherit the Wind was nominated for four Academy Awards."€

As relatively innocuous as

Creation is, the film's producer had a great deal of trouble finding a U.S. distributor for this chamber piece -- every other country in the world signed up first, but the U.S. shied away. Evolution, the bane of the American religious right, is the reason. As he

complained to the London

Telegraph: "It is unbelievable to us that this is still a really hot potato in America."

Ebert worried that Amiel restrained himself from fashioning a more powerful film "€œin fear of provoking controversy." Ebert'€™s irate question lingers on: "œHas it gotten to that point?"€ Perhaps the best reason to take a look at Creation is that it can piss off the creationists.